When Back Pain Is Not a Spine Problem | Causes Beyond the Spine

When Back Pain Is Not a Spine Problem

By Natalia Skizha

Neurosurgeon

Medical Author at Briefor Health

Not all back pain originates in the spine

Back pain is one of the most common reasons for seeking medical care worldwide. Understandably, many patients assume that pain in the back must originate from the spine itself. In clinical practice, however, this assumption is often incorrect.

A significant proportion of back pain cases are not caused by structural spinal pathology.

Recognizing this distinction is critical for avoiding unnecessary investigations, ineffective treatments, and delayed recovery.

Why back pain is frequently misattributed to the spine

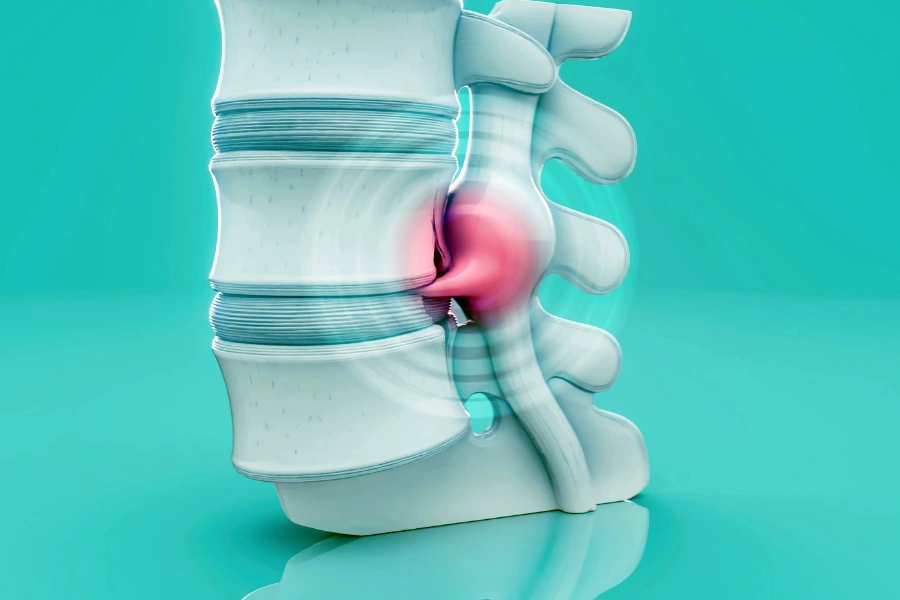

Modern imaging has increased the detection of spinal abnormalities, but it has also created a diagnostic bias. Disc bulges, degenerative changes, and minor protrusions are frequently identified on MRI — even in individuals without symptoms.

When pain is automatically attributed to these findings, clinicians risk overlooking non-spinal pain generators that require a different diagnostic and therapeutic approach.

Muscular and myofascial sources of back pain

One of the most common non-spinal causes of back pain is muscular dysfunction.

Muscle-related pain may arise from:

- prolonged static postures;

- repetitive strain;

- inadequate core stabilization;

- stress-related muscle tension.

Myofascial trigger points can produce pain patterns that mimic nerve compression, yet imaging often appears normal or shows incidental findings unrelated to symptoms.

Sacroiliac joint dysfunction

Pain originating from the sacroiliac (SI) joint is frequently mistaken for lumbar spine pathology.

Typical features include:

- pain localized to the lower back or buttock;

- discomfort aggravated by standing or walking;

- pain that may radiate to the thigh but not below the knee.

SI joint dysfunction does not appear clearly on standard MRI and requires careful clinical assessment.

Hip pathology presenting as back pain

Hip joint disorders, including osteoarthritis and labral pathology, often present with pain perceived in the lower back.

Key clinical clues include:

- pain triggered by hip rotation;

- reduced range of motion;

- groin discomfort accompanying back pain.

Failure to examine the hip may result in misdiagnosis and ineffective spine-focused treatment.

Visceral and referred pain

Certain internal organ conditions can produce referred pain to the back, including:

- renal pathology;

- gastrointestinal disorders;

- gynecological conditions;

- vascular abnormalities.

In such cases, spinal imaging may be entirely normal, and persistence of symptoms despite musculoskeletal treatment should prompt broader evaluation.

Psychological and central pain mechanisms

Chronic back pain is not always driven by ongoing tissue damage. Central sensitization, anxiety, depression, and stress can amplify pain perception even in the absence of significant structural abnormalities.

This does not imply that pain is “imaginary.” Rather, it reflects the complexity of pain processing within the nervous system.

Ignoring this dimension often leads to repeated imaging, escalating interventions, and patient frustration.

When spinal surgery is not the answer

Surgery addresses structural compression or instability. When pain originates outside the spine, surgical intervention is ineffective and potentially harmful.

Clear surgical indications require:

- consistent neurological deficits;

- radiological–clinical correlation;

- failure of appropriate conservative treatment.

Back pain without these features should prompt reconsideration of the diagnosis.

The importance of a comprehensive clinical evaluation

Effective diagnosis of back pain requires:

- detailed medical history;

- physical and neurological examination;

- functional assessment;

- selective use of imaging;

- openness to non-spinal explanations.

A neurosurgeon’s role is not only to operate, but also to identify when surgery is unnecessary.

Conclusion

Back pain is not synonymous with spine disease. While spinal pathology is an important cause, it is far from the only one.

Accurate diagnosis depends on recognizing when pain originates from muscles, joints, internal organs, or central pain mechanisms — rather than from the spine itself.

Understanding this distinction protects patients from unnecessary procedures and guides them toward effective, individualized care.